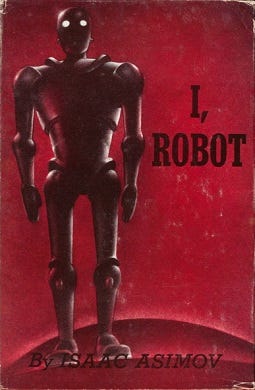

Exploring Isaac Asimov's Three Laws of Robotics

In Isaac Asimov's novel I, Robot, the Three Laws of Robotics govern machines. What ethics and guidelines govern today's AI?

“Sizzling Saturn, we’ve got a lunatic robot on our hands.”

Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot is a collection of short stories written from 1940-50. The stories are linked by an interview with robopsychologist Dr. Susan Calvin who recounts case studies highlighting robot development and evolution over her 50 year career.

There’s the case of the little girl who grew attached to her silent but friendly robot caregiver, Robbie; an advanced robot working on an asteroid mining facility believes he was created by The Master and forms a religious cult; a Brain builds a spaceship capable of interstellar travel endangering the lives of two engineers; a local politician might actually be a robot.

The through-line in these stories are Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics.

The robots struggle to balance the three laws when faced with ambiguous or contradictory instruction, or various external factors, leading to abnormal behavior. In each case study, Calvin or her colleagues identify an issue with the robot, troubleshoot the potential cause as it relates to the three laws and figure out a solution. As robots become more advanced, we see how their evolution affects human civilization, for better or worse.

At the end of the novel, Calvin is faced with the question of why Machines governing the world economy caused slight errors. The Machines are computing devices - robots aren’t used on Earth - so it’s merely outputting data which humans implement. Calvin realizes that in accordance with the first law, the Machines are moving humanity away from conflict toward a more peaceful civilization, but that it cannot explain itself because to do so would also harm humans (humans don’t like change much). Ever so slightly, the Machines take the reigns for humanity, perhaps for the better because we couldn’t do so for ourselves. Whatever the ultimate outcome, Asimov demonstrates that once humans create the robot, our futures are linked, with humanity’s survival hanging in the balance.

I started thinking about how AI has become an integral part of nearly every industry here in the United States. We can take AI to an Asimovian conclusion where the Machines take over the world for the good of humanity. But this presupposes that the humans who made the rules governing the robots in the first place were good, decent humans who understood the dangers of such advanced technology but also the opportunity for the advancement of the human race with robots and machines helping us. That’s not to say that there won’t be failures, malfunctions, and problems to overcome, as in Calvin’s case studies.

So, similar to the Three Laws, how are AI and robotics companies setting guardrails for their technology’s use?

I asked Chat GPT to explain it’s ethics and guiding principles:

Open AI’s Charter and Usage Policies emphasizes the company’s belief that their technology should “benefit all of humanity”.

Similarly, I wondered about the rules and ethics governing Boston Dynamics robots:

Recently OpenAI technology was purchased by the Pentagon. Perhaps there’s a distinction to be made here between language models versus other forms of artificial intelligence but it’s not hard to imagine where this could end up in the near future. Boston Dynamics doesn’t deploy weaponized robots to the military but that doesn’t mean there aren’t other companies which do so.

There’s been plenty of documented cases where ChatGPT answered with all sorts of gibberish or when Bing told a reporter it loved him and when a software engineer thought Google’s AI could be sentient. Researchers bypassed the chatbot’s programming despite Open AI’s guardrails setup to prevent misuse. On the other hand, in a recent study ChatGPT diagnosed patients with a higher success rate than doctors.

In I, Robot, the three laws were built into the positronic brains of the robots. What specific software restrictions are deployed in Boston Dynamics or ChatGPT which compel it to do no harm? Are there instances where human-imposed guardrails fall short causing the robot or AI to miscalculate in error? When AI becomes too advanced for our own understanding, who will be accountable for it? The tech companies? The AI? The broader public?

AI and robots have the potential for failure and misuse but also for enormous positive changes in our society. I hope we’re smart enough to recognize the difference.

Until next time,

Keith